Design is much more crucial than many people realize. It is not merely something that dresses up information; design is how users interact with data. In professional and technical fields, we sometimes make the mistake of thinking that we can get something to work and then just make it pretty and useable later. This is a major conceptual flaw, as elaborately argued by Apple CEO Steve Jobs: "In most people's vocabularies, design means veneer. It's interior decorating. It's the fabric of the curtains of the sofa. But to me, nothing could be further from the meaning of design. Design is the fundamental soul of a human-made creation that ends up expressing itself in successive outer layers of the product or service," and again simply: "Design is not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works." This view of design is a significant reason why whether you love or hate Apple, they are one of the most valuable companies in the world, and almost certainly the most culturally significant. More than perhaps any other company its size, Apple has an understanding of the importance of interface and design, and how they are inextricable from function. Bad design also has a pragmatic impact. Read this post about the recent Tropicana juice package redesign. Then read this post from kottke.org (including links) about how PepsiCo was compelled to undo its product redesign because it stunk. Notice that the objections really don't have to do with how pretty the designs are; the comments have to do with how design actually facilitates or hinders access to the product. You might think this is minor, but PepsiCo is a giant company, and they just had to issue a major mea culpa and change the product design back because of consumer response. This is not a situation that you would want to be in as a designer. The point here is often discounted, but it is absolutely correct and clearly has tangible business implications: design matters, because design is product interface. Our products are documents, and design is no less important in this context. A person could devote a lifetime to studying design, but there are some simple principles that can be grasped quickly and that make a huge difference in documents. Qualities of Good DesignFirst, good design is invisible. This means that good design allows readers to pick up a document and find the information they want effortlessly. When was the last time you picked up a document and thought "Wow, this is really well designed!" It is more likely that because it was well designed, you picked it up and started obtaining the information you wanted. Only when there are problems with the design—say, the alignment is off or the contrast is bad—would you notice the design. This is not to say that your brain isn't responding to the design. Design is noticed by the brain, but it happens more quickly than we can realize and articulate. For example, this BBC News story reports that viewers make judgments about website design in about one 20th of a second. The frame established in this snap judgment, which is made before any kind of content transmission can occur, dictates the viewer's relationship to the document. Therefore, the second quality of design is that good design is persuasive. It persuades or dissuades readers from reading your document. It also lets them know how professional, credible, and competent the document is. Good design establishes the ethos of a document before any of the content has an opportunity to do so. Though people may not be aware of it, good design will make them trust you and your information more. Think how you know when an email is phony. It is almost always mechanical issues (spelling, strange title, awkward prose) that tip you off before you actually read the content (that is, if you haven't already identified the email as phony and moved on). The third quality of design is that good design guides the eye. It helps direct readers' line of vision to follow the relevant tasks in the relevant order. It helps readers find the most important information effectively. It removes all visual clutter and helps readers focus on what they need to know. We will analyze good and bad instructions to explore this. Bad directions confuse you so that you don't know where to look and how to proceed. Good directions, conversely, guide you from one step to the next. In guiding the eye, it is not just the text, bullets, lines, and graphics that help, though these elements are important. White space also guides the eye. This is because of the fourth quality of good design: good design incorporates white space effectively. White space is not empty space to be filled with content, but part of the overall design. It establishes the contrast that makes content meaningful. This article on white space from A List Apart provides a useful discussion of how white space functions as a design element. So as you design, think about white space. Your readers will respond to it (consciously or not), so you are responsible for using it well. Design is frustrating, because after you conceive and execute your design, you still have to go back over everything carefully to make sure that every little detail is worked out. Quality five is that good design requires careful attention. The grading standard for your instruction sets is that they could operate within the professional world. It's a high standard, but also necessary for success in current and future employment. Therefore, the difference between an A and a B project will often be the extra hour you spend printing out and revising your instructions to fine tune every detail. Design ExampleLet's look at an example of how design principles show up in documents. Say you were writing instructions about what to do if you encounter a bear:

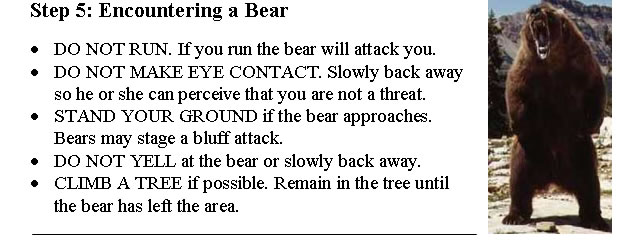

This passage has some problems that may not jump out but that affect the design of the section. First, the design has a problem from a context standpoint. Who, when facing a wild bear, is going to sift through this paragraph and grasp all these details? Panic will overwhelm cognition, so information needs to be perceived as quickly as possible. Second, why is "DO NOT RUN" halfway through the paragraph? That likely is the reader's first instinct, so it needs to be addressed immediately. Third, the design has problems from a design principles standpoint, which end up affecting usability. There is an alignment problem—the line across the bottom does not sync with the bottom of the picture. Also, lack of consistent repetition is a problem. Some steps are capitalized and some are not. Contrast is also an issue, because the title of each step is smaller than the step's instructions. It is not easy to extract data from this example, because design is how the reader interfaces with the data. Seemingly small issues may not necessarily matter to someone facing a wild bear, but which bear encounter manual will people trust: one that is professional and flawless or one that looks like it was slapped together in PowerPoint and reproduced on a photocopier? Details establish an overall ethos. In a professional situation, this means the difference between success and failure. A revision of this work might look like this:

This is not necessarily the ideal design, but you can see improvement, and you can probably identify other potential improvements as well, such as adding a more usable graphic, aligning the top of the picture with the title, and fixing the contradiction between standing your ground and climbing a tree. More importantly, you are now able to articulate the improvements based on usability and design principles. Remember these design principles as you put your project together. Good design leads to improved usability and ethos, and will persuade users to read your document. |

Calendar >